|

The 36-speed screwcutting gearbox was driven through an ingenious and highly refined leadscrew reverse mechanism mounted beneath the headstock. This mechanism incorporated both a single-tooth dog clutch and a set of "synchro cones" to smooth out its engagement. The cones engaged momentarily to bring the dog clutch up to speed, then withdrew to allow the dogs to engage gently - this provided a perfect pitch relationship every time and without the heavy clunking of a conventional leadscrew reverse. So effective is the arrangement that it's possible to reverse the leadscrew instantly at 600 r.p.m. without the slightest crash or complaint from the lathe. The whole mechanism is a pleasure to operate, being light and positive. The carriage is fitted with an auto-knock-out bar, with adjustable stops for the longitudinal movements, meaning the lathe will stop feeding or threading automatically at any preset position. Combined with the standard-fit crosslide stop this makes cutting any thread, no matter what the pitch or cutting speed, easy and foolproof.

Although most examples of the lathe were fitted with imperial leadscrews, a metric version was available, as were metric transposing changewheels for the imperial models. These gears were carefully thought out and consisted of a 127/120 compound gear and 45,54,63,72 tooth drivers. The 72 was supplied with the machine as part of the standard imperial geartrain with the others purchased separately.

Like the rest of the lathe, the apron was beautifully made and well-specified. Feeds were engaged by raising levers that were feather-light in operation and yet beautifully positive. The half-nuts were well-supported and their engagement equally delightful to operate. Despite being very advanced for its time, the double-walled apron was partially open at the rear, but did incorporate an oil bath for lubrication in addition to various oiling cups. It was well protected from the entry of swarf and the pinion had an outboard bearing where it engaged the rack, meaning it was nigh on impossible to overstress.

Sadly, the cross and top slides were not provided with taper gibs, yet still slid easily and with precision. The crossfeed screw had its thrust bearing at the rear and was hence operated in tension, preventing wind-up under heavy cuts. Additionally, on the 18-speed models, the block in which the bearing was mounted could be released by loosening one screw and attached quickly to the supplied-as-standard taper-turning attachment, enabling taper turning whilst retaining the full function of the crosslide. The 12-speed lathe was not quite as refined, but had a similar mechanism that was just as well thought out - although the taper unit itself was optional. Dials on both slides were large for the era and very easy to read, with deeply engraved scales.

The Hendey tailstock incorporated a very effective, patented, lever-clamping mechanism to grip the bed along with a double-split clamp to lock the very large diameter MT3 barrel. The barrel was beautifully engraved in divisions of 32nds of an inch along the length of its 5-inch travel. Thrust was taken by a plain cast iron bearing surface that was automatically oiled at the same time as the barrel and screw. Although very simple, it was well thought out, the action being very light and smooth under all conditions.

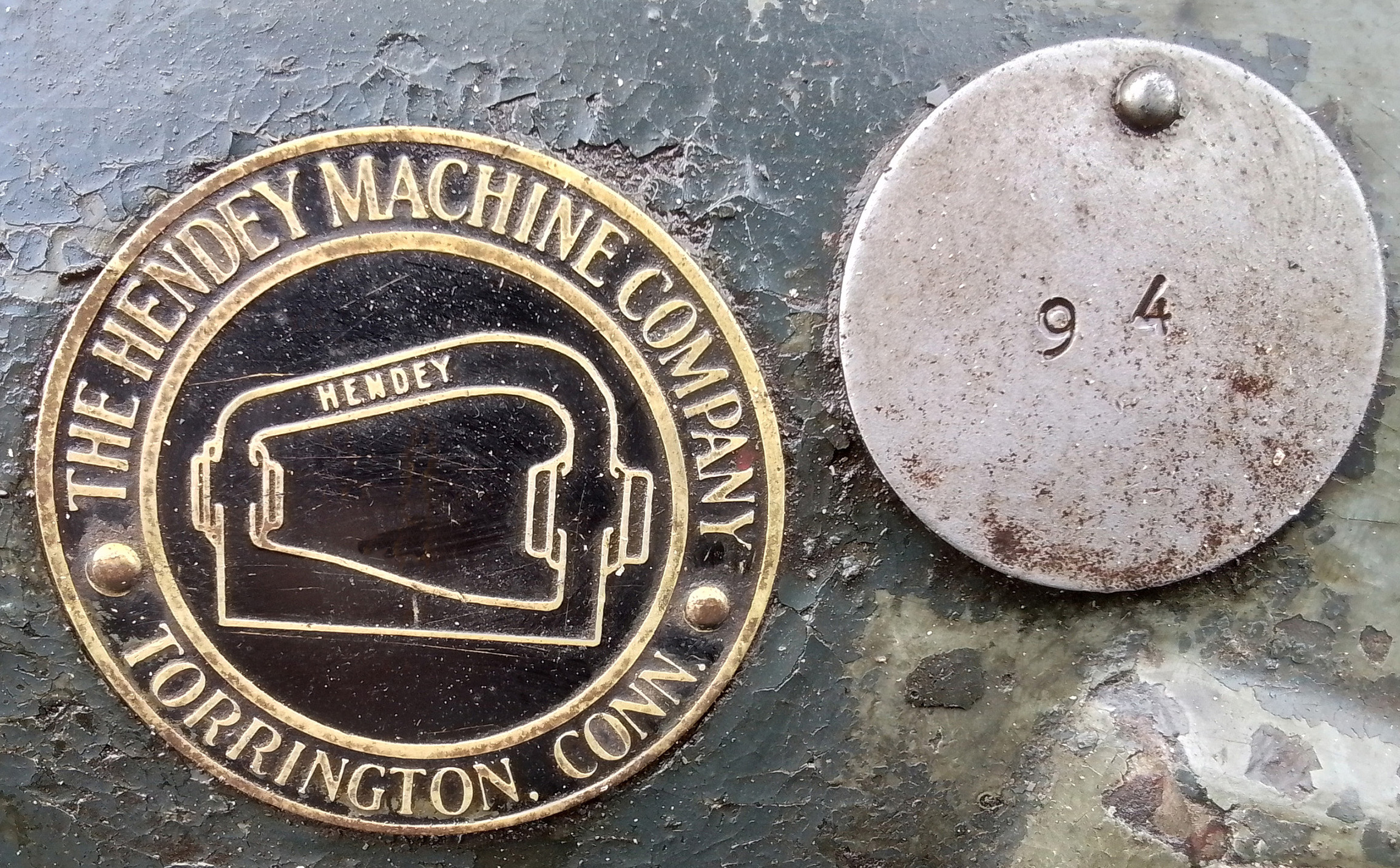

Such is the quality of the Hendey, that the writer's scruffy and flaky 12x30 still runs very quietly and with uncanny fluidity in every respect - despite 83 years of use, of which 20 plus were spent in a damp garage. The cast iron has cleaned up to like new and every single part appears to be stamped with the same serial number to identify it as belonging to that individual machine. These lathes were joyful to operate when new and, arguably, a viable alternative to the far more common makes of Holbrook, DSG or Monarch - to name but a few of the best lathes ever made.

|

|