www.lathes.co.uk

The Adept Lathe

© Andrew Webster a.webster@sympatico.ca

Introduction

This document

provides an introduction to the little Sheffield-made Adept modeller’s lathe,

built in large numbers[1]

and, while constructed down to the lowest price, many thousands survive in use

or awaiting restoration. This document,

therefore, is primarily meant to assist restorers and users of this attractive,

crude, and definitive “cheap lathe”. An updated PDF version of this article –

with additional background data - can

be downloaded here

Pre-History of the Adept Line

The origin of

the Adept lathe can be found in the Models A and B Heeley-made “Portass” lathe

introduced in 1926 and produced for under a decade. The Heeley Motor and Manufacturing Co. took its name from a

former cluster of villages now a suburb in the south of Sheffield, but it was founded ca. 1889 by Charles

Portass. The familiar Portass brand

appeared ca. 1926, but as a line of lathes built by the firm Heeley before a

firm named Portass existed. This

2-1/8" plain “Portass lathe”, soon nicknamed the "Baby Portass",

was briefly described in the 22 Apr 1926 Model Engineer. I own one of these machines. They were popular during the decade they

were in regular production.[2]

The early history of Portass lathes

concluded when the Heeley business was split, following the founder' death in

the late 1920s, between Portass sons Stanley and Fred. Portass Senior may have died in the 1920s

but the firm was not split until 1930 or 1931.[3] Stanley Portass renamed the existing Heeley

firm the Portass Lathe and Machine Tool Company and moved into the still extant

"Buttermere Works" off Abbeydale Road, near Millhouses. The Portass Lathe and Machine Tool Company

continued the development of the 3rd generation of Heeley lathes and

also added new models. The firm also

produced large machine tools, and all Portass machines regardless of size were

characterised by massive castings and known for their rigidity.

After

the Heeley split, Portass brother Fred commenced trading as F.W. Portass,

producing tiny, inexpensive machines for modellers: the Adept line. Fred

Portass, with less money to work with, made the tiny machines in a much smaller

Abbeydale works not far distant from his brother’s in Sheffield. Fred miniaturised the cantilever bed

architecture of the 2-1/8” ‘Baby’ Portass, creating much smaller and lighter

machines with brilliantly engineered castings.

Stanley Portass has bigger fish to fry and never attempted to compete

with his brother for the tiny sized modeller’s niche. His smallest product, the Baby, was comparatively massive and far

heavier. Its successor, a longer 2-1/8”

lathe with a double-footed curvilinear bed, made no attempt to match the Adepts

for compactness or lowest possible price.

Both Portass brothers were conservative in their design

philosophies, refusing to modernise in the face of vicious competition after

WW2. Stanley made minor changes which

allowed him to continue business until the early 1970s. Fred changed hardly anything, apart from

introducing improved hand shapers (his other core product) and ceased

production about 1961.

‘Baby’ Portass: Predecessor of the Adepts. Model

Engineer 22 Apr 1926.

History of the Adept Line

Two versions

of the Adept lathe were made by F. W. Portass: the "Adept" (ordinary

model, with bolt-on simple slide-rest) and the more complex and expensive compound

slide-rest and leadscrew "Super Adept" model. The Ordinary appeared about 1931, available with a plain,

lever, or screw tailstock. The Super

Adept appeared at the August 1933 Model Engineer Exhibition, at the

Bond's o' Euston Road stand. This firm

billed itself as "the Home of Hobbies" and sold "everything

'modellish'" for four decades. The

14 September 1933 Model Engineer reported that "their principal

exhibits in the lathe line comprised practically all the models made by

'Portass'. Notable among these last

were a new specially made lathe called 'Bond's Maximus', a 3 in. back-geared

S.C. lathe...at the other end of the scale was the one and only entirely new

'Adept' lathe of the same make, which is now designed with a sliding saddle,

carrying the compound rest. This is

illustrated, but price on application."[4] The latter marks the introduction of the

Super and the start of several decades of confusion between the two Portass

firms who, probably by arrangement, catered to different parts of the market

and periodically sent one another misdirected correspondence.

Tyzack Ordinary Adept advert, plain tailstock,

ca. 1935.

The

Great Depression caused a rapid die-back of the multitude of small British

lathe makers who appeared right after WW1. For the most part these firms produced machines of undistinguished

quality and design. Of the model

engineer class producers, Stanley Portass’ well-capitalised firm thrived, as

did newcomers Ross & Alexander and Myford.

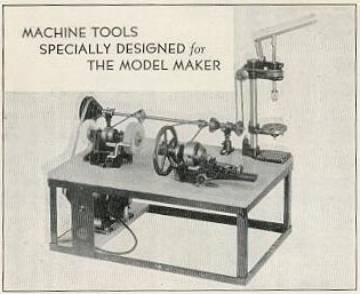

The two Adept lathes occupied the model-maker’s lathe void when the Baby

Portass and its competitors vanished, and filled this void until copycat competition like the

Flexispeed and Wizard appeared in the late 1940s. But the initial rise to popularity of the Adept products, during

hard times, was quick because they were priced to sell. Until the early 1950s it was difficult to

engage in scale railway modelling in the absence of a small lathe, and model

engineering was out of the question.

How

common were small lathes in these hobbies?

In 1937 a bare-bones, ordinary Adept cost a mere 13/-9 (60p or

$1.25!). It included a hand turning

rest, two unhardened centres, plain tailstock, and a faceplate. For 22/- you also got a bolt-on slide-rest

(a quarter of an average weekly industrial wage) and for 15/- more an

independent 4-jaw chuck capable of precision if the work was carefully

centred. No other manufacturer

approached the prices of the Adepts. It

is fair to say that these machines did more than any other to put miniature

machining within the grasp of the ordinary man. These little (13” long) cast

iron machines were the archetype “small lathe” for modellers and model

engineers lacking space and money. Fred

Portass soon advertised them correctly as “world renowned”. Examples have been found in Holland, South

Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and America.

Like

most of the other makers, Fred Portass advertised his products aggressively in

1939, already emphasising "world renowned". Then the War came.

Commercial model production plummetted in 1940, when Fred Portass still

regularly advertised Adept lathes using the familiar plate depicting the

popular Ordinary with a non-screw tailstock.

In June the Ordinary was 24/- with slide-rest and 15/- with just a hand

rest, screw tailstock 6/- extra. The

Super was 35s. 6d. and the 4-jaw chuck 16/-.

In 1941 he less often advertised that Adepts were "Still available

though we regret we cannot give our usual prompt deliveries, owing to the

urgency of Priority Orders for Government Work”.

The

production of metal toys was banned in January 1942. So too, a year later, was the commercial sale of new or second

hand models, either whole or as components.

Unable to buy manufactured items, amateurs were desperate for lathes to

make their own components, but the sale of new machines now required a licence

attesting to their use in war work.

Persons still modelling used discarded or hoarded material, aided by a

weak private trade in used models. The Model Railway News shrank to 14 tiny,

thin pages but the Model Engineer,

its sister publication, fared better because model engineers were sought in

armaments factories. Practitioners like

Edward Beal and L.B.S.C. kept writing, furthering techniques and keeping up

morale.

Model

engineering firms made war supplies such as fuses and aircraft

instruments. So did machine tool makers

whose products were not up to the needs of military establishments or

factories. This probably included the

firm F.W. Portass. By September 1947

the firm was again supplying Adept lathes to the public but advising of a 12

month wait list after placing an order, on account of being “inundated with

orders”. In fact, the Austerity decade

had begun, and materials were in short supply.

Five years of pent-up demand exploded and any lathe seemed worth its

weight in gold. The Adepts, still the

cheapest, sold vigorously.

Unfortunately Fred Portass, made complacent by this surge in demand,

failed to modernise his designs or increase his tiny range of accessories when

a host of competitor lathes began to appear.

Worse, he failed to advertise in the model engineering press until 1950

when new competitors were long advertising aggressively. By then, various new small lathes,

especially the new 1-5/8” Flexispeed and the 1-3/4” Lane (formerly the

'Wizard')[5],

were clearly taking a substantial bite out of the Adept’s market share.

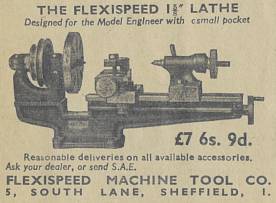

Lane and Flexispeed Adverts, from

the Model Engineer, ca. 1948.

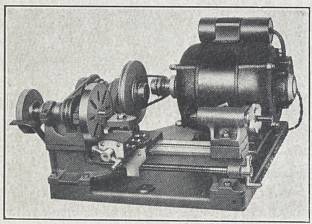

There

were others too, of comparable size, like the gimmicky Grindturn with an

ill-advised extended spindle bearing a large, unprotected grinding wheel beside

the head bearing! At first, the Adept’s

new competition tended to be better-specified or at least more highly-featured,

and more expensive, and so less of a threat to the Adept line.

Grindturn 2” Model ca. 1947. One of the high-specified, more expensive

small lathes.

Flexispeed

steadily worked towards market superiority.

In 1947 their 1-5/8” model was adopted by Tyzack as the new Zyto small

lathe. The major distributor Garner

began promoting Flexispeed products on favourable terms, not mentioning Adepts

which they also carried. The year 1950

telegraphed an irreversible decline of the fortunes of the Adept’s maker. The main agent of this decline was Flexispeed

who now moved strategically to occupy the niche held by F.W. Portass.

Flexispeed

took out a half-page advert promoting their Adept-like 1-5/8" models and

budget horizontal bench mill (£20), an item that Fred Portass ought to have

introduced. The Standard Flexispeed

lathe was £7-6s-9d. with back-gearing for £2 extra. Fred Portass did not try to compete with this higher-specified

and costlier machine, evidently feeling secure that established name and

experience as the lowest priced lathe would see them through. Yet Flexispeed had more surprises. They introduced a 'Student' 1-5/8"

lathe for just £4-17s.-6d., almost the same price as the Super Adept. This was the first ever real attempt to

build down to the Super Adept's price, although no one tried to out-beat the

simpler Ordinary Adept. By then it

hardly mattered because buyers expected more and the Ordinary was becoming too

elementary. The Flexispeed Student's

tailstock ran on the bed dovetail, not in a slot, making for more consistent

alignment than the Super Adept. The

larger (1/2” vs. 3/8”) spindle was drilled through and accepted standard 0MT

tooling. Yet no compound top-slide and

spindly bed casting still made the Super Adept more lathe for the money.

By 1953

the Adept’s distributors seldom ever mentioned Adept lathes in their

advertising, possibly prompting Fred Portass to regularly advertise in the ME

using the familiar, archaic engravings.

By 1953

the name and address of Fred Portass' firm had changed to "F.W. Portass

Machine Tools Ltd., Adept Works, 55 Meadow Street, Sheffield 8". The reasons for the apparent relocation are

unknown but a brand makeover was certainly being attempted. Stung by new competition, Fred Portass was

now regularly advertising in the M.E.

He still emphasised "world-renowned", "world

famous", and "full range of accessories" including a new

three-point steady. The expansion to

his accessories list was too little, too late.

Despite competition from, Robblak, Cowells, and other firms, Adept

shapers remained popular and for a while this offset some of the losses in

lathe sales.[6]

Flexispeed

was now in cutthroat competition with F.W. Portass. In 1953 they carried a similar advert for their 1-5/8"

lathe, priced down to £5.17.6. versus £5. 15s. 0d. for the Super Adept. Flexispeed's independent chuck was £1. 17s.

6d. versus £1. 18s. 6., and Flexispeed offered a tailstock die holder (15s.

0d.) which Adept did not. Flexispeed's

steady, at 11s. 6d., was 3s. 6d. more than while the Adept. Fred Portass was losing the lathe price

advantage. What is more, the Flexispeed

had a larger (1/2") hollow mandrel and better alignment due to a tailstock

running on a dovetail bed. The Adept’s

lug-in-groove had a reputation for being a sloppy fit.

This was

the Jurassic of the little, cast-iron lathe.

Only the evolving Flexispeed would survive the impending die-back. As the 1950s progressed, most of the British

makes of traditional modeller's lathes disappeared. Notwithstanding the occasional interesting but not revolutionary feature,

these machines remained grounded in turn-of-the-Century design and

manufacturing technology. In 1954 this

obsolescence became clear when the early Unimat (DB200/SL1000) appeared in the

UK. This had 1.42" centres with

6.75" between centres. The machine-cast

alloy castings were generally superior to the old sand-cast iron type. Best of all, the Unimat looked modern, had a

self-contained motor, and came with numerous accessories such as the elusive

3-jaw scroll chuck. By then the tired

old Adept, with few accessories, called for more patience and machine-shop

acumen than modellers of the day were prepared to accept. They now sought a “universal machine tool”,

and while the Adept assuredly was not, neither were most of the machines which

claimed to be.

Production

of Adept products ceased about 1961.[7] Some dealers a few some in stock for several

more years; in itself a statement about how demand for this type had

plummetted. Improvements kept the

Flexispeed line selling into the 1970s,[8]

but by without doubt the new archetype was the evolving Unimat. Machines such as the Flexispeed and Unimat

did not do the firm F.W. Portass in.

Fred Portass did his own firm in.

When attractive, modernised small machines appeared in the late 4040s

onwards, the Adept slid towards oblivion because its maker failed to modernise

the design. It would have been simple

to offer as extras features like back-gearing, a decent vertical slide

accessory, indexed handwheels, integral motorisation, a larger ½” diameter spindle

drilled through and with a full 0MT taper, or a spindle pulley with index holes

and a locking pin.

Specifications of Adept Lathes

Adepts were produced under basic

conditions which limited the size and complexity of the machines produced. Precision lathe authority Peter Clark

comments on their origins: “Years ago…a friend of mine, told me about visiting

the Adept maker, Fred Portass at his little workshop in Abbeydale Road,

Sheffield. The story was that Portass

started with only two machines. These

were a small capstan lathe of 5/8" capacity and a single-geared lever

operated bench milling machine. The

design of the Adept was supposed to have been governed by the capacity of these

two. Certainly the cast iron used was

beautiful stuff that could well have been necessary for milling on a tiny mill,

using one cut!” Somehow, he found ways

to organise production around basic equipment such that he could produce large

volumes of machines at consistently low cost.

Adepts were the cheapest and most

rudimentary miniature lathes to have seen sustained production.

Adept lathes

have 1-5/8” swing (3-1/4” diameter) over the bed. The gap in the bed admits material 4-1/4” diameter. Six inches between male centres at maximum

tailstock set-back. Spindle and tailstock

barrel are 3/8” mild steel running in cast iron housing without bushings; many

owners bored these out and fitted bronze bushings. Articles on Adept improvements from the M.E. showed how to make

this, and other improvements, with no machines beside the Adept itself.

Cast iron's most striking

characteristic is its high resistance to sliding wear. Few lathes of the time featured pre-stressed

ball or roller bearings. These were

costly in the smaller sizes until the 1950s.

The better large lathes therefore often had replaceable bushings of

bronze or gunmetal, but many gave excellent service with a hardened and

polished steel mandrel running in a lapped iron split-housing. Most, if not all, of the small model-maker's

lathes had an unhardened mild steel spindle running direct in an iron

housing. These were seldom polished or

lapped, and the sometimes the housing was bored without reaming, like the

Adept.

This being said, the longevity of

this arrangement is remarkable if attention was paid to cleanliness and

lubrication. It is nevertheless likely

that an Adept or similar spindle will exhibit significant wear, especially at

the tail housing where an excessively heavy chuck could cause headstock centre

drop. Some owners fitted cycle oil cups

which did much to keep things oiled.

Some fitted fibre shims to stop oil running quickly out of the sawn

housing. Others neglected the oiling,

paid no attention to iron and corundum dust, and responded to heavy wear by

screwing the housings together until they fractured. This is a common fault on small, old lathes.

The Adept’s

spindle nose is threaded an uncommonly small 3/8” BSF. The spindle and tailstock barrel are both

3/8”, so it was a simple matter to fit up some 3/8” steel in the headstock and

turn up special-purpose barrels. Owners

of plain and lever tailstocks were especially apt to do this. Many Ordinary Adept owners had only a plain

tailstock with just a point. They

drilled many a hole by centre-popping the butt end of a drill, holding in a

tap-wrench, and forcing in with brute force by pushing on the hand wheel. Clever owners turned up a female-centred

tailstock barrel.

Tailstock and

mandrel have 0MT-angled tapers but regular 0MT tooling will not fit. This is because, in order to get a socket in

a tiny 3/8” mandrel, Fred Portass extended the small end of 0MT so that his

sockets, while the right inches-per-foot taper for 0MT, have a large diameter

of ¼ inch while the small end of a standard 0MT taper plug is 0.252 inches. This conclusion follows inspecting a dozen

Adepts and a report from someone who visited the works just after the War. The non-conformity prevented Adept owners

from using the wide range of standard 0MT taper tooling carried by tool shops

in the 1930s to 1950s. (Aside: Curse Mr.

Morse for his system of tapers with approx. 1.5° included angle but varying

several thou per foot! God bless Mr.

Jarno and his entire family for inventing a rational taper consistent for all

sizes of socket. A fatwa upon lathe

builders who still cling to the Morse system.)

The Super

Adept was preferred when finances permitted, but the Ordinary version appealed

for reasons beside low price. It was

ideal for workers (e.g. doll-house and pen makers) only interested in

hand-turning against a T-rest. They

needed little extra besides chisels or gravers, a prong centre for wood

turning, and maybe faceplate or drive-plate with carriers and male

centres. When required for metal work,

the T-rest could be unbolted and replaced with an optional slide-rest.

Ordinary Adept ca. 1937 with screw

tailstock. Before restoration by A.

Webster.

The Ordinary

Adept’s slide-rest top slide rotates for taper turning (same item as on the

Super). The lower slide’s base has a

cast iron lug which fits into a 3/8” milled slot machined down the centre of

the bed. All WW (Webster-Witcomb)

pattern watchmakers' lathes have a bolt-on slide-rest, so this idea was hardly

new. Some American WW lathes of the

time (e.g., Mosley, Peerless) had a central slot to guide lugs beneath both

slide-rest and tailstock; the bed was not prismatic form, meaning that there

was no outside surface for guidance as with, say, a Boley WW or a Levin.

The Ordinary

Adept shares with such machines the disadvantage that a bolt-on slide-rest

permits only a limited length of cut to be taken. Many users would find this no limitation at all. On a positive note, All Adepts have a cast

iron English Pattern toolpost. While

lacking the adjustable jackscrew found on, say, the Myford or Flexispeed, it

can clamp a wide range of tools, tool-holders, and work pieces. The Ordinary Adept's extraordinary cheapness

stems from well-executed castings, few parts, and few exacting machining

operations. The headstock was made as

accurately as the Super version, and well-aligned with the ways, elsewhere the

quality control could be lacking.

It seems that

the better castings went into Supers while Ordinaries often got the ones with

roughness, non-critical fissures, or pits.

Parts also seem to have been sent the Ordinary Adept assembly line when

machining revealed a void in the casting.

I have seen an Ordinary Adept with matching, undersized female

tapers. The angle is right but the

holes are not bored deep enough to grip more than the end of a regular Adept

male centre. This strongly suggests

that Ordinary Adepts were sometimes built from parts not good enough for the

posh model. The Ordinary was often

gaily painted, at the request of distributors, in order to camouflage its

deficiencies. I have one in vile cream

with handwheels picked out in green, but others have red highlights. The Supers are sometimes described as

characteristically black stove-enamelled.

In fact the most common colour was dark blue. I have three of that colour.

Do not let

these occasional deficiencies dilute your enthusiasm. Many surviving Ordinary Adepts are quite serviceable for

purposes like turning H0 scale or 4mm scale locomotive fittings. They were not been built for more accuracy

than this. Remember also that S.C.

Pritchard did the experimental work for his PECO products on an Ordinary Adept,

during the War and on his dining room table.As when they were new, fitting and

bodging are called for when greater precision is demanded. One of my Ordinaries arrived with bearings,

spindle, and tailstock barrel as good as a Super Adept that I had extensively

tweaked into top condition.

The more

popular Super Adept features the same compound slide but atop a saddle (or

carriage) which is driven by a full-length leadscrew. The three slides have

adjustable gibs made of press-flattened steel strip. The saddle runs smoothly and accurately on outside-vee'd ways

which do not feature on the Ordinary version.

The saddle is propelled by a left-hand leadscrew whose hand wheel has a

pleasant, properly-waisted handle. The

central slot of the Ordinary Adept remains to guide the tailstock's lug. This is severely prone to wear, but the

solution is simple: File it off and screw on a block of steel that fits nicely

between the ways.

The Super is

a much more useful machine than the Ordinary.

The tool bit can traverse the full length of a six-inch rod held between

centres. The top-slide can be set to cut a taper yet ordinary 90° x-y turning

can still be done by means of the saddle and cross-slide leadscrews. This is handy when making tailstock tooling

like a drill pad. The top-slide can be

removed and an angle plate put in its place for simple drilling, boring, and

slot-milling. With some bodgery the

top-slide can be mounted on the manufacturer’s angle plate, thus making it a

vertical milling attachment. No other

little lathe offered this simple, cheap facility.

Super Adept carriage, showing vee-ways and

top-slide. Collection A. Webster.

Super Adept on test bench after restoration. Collection A. Webster.

Super Adept headstock. Note the light 4-jaw chuck.

Collection A. Webster.

Variations of Adept Lathes

The Adept

lathe may have been sold, or even produced, in the U.S.A. by the Adept Tool Co.

of 2342 Hampton Road, East Cleveland, Ohio.[9] This firm illustrated an Ordinary Adept

lathe fitted with the firm’s own low-speed, backgear replacement system

involving an extended spindle with 6” pulley, driven from a 1” pulley on a line

shaft. An unremarkable looking “Adept

sensitive drill” was also illustrated, but this may have been a product of

Adept Tool Co. rather than F.W. Portass.

The Super is known to have been produced by F.W. Portass in the 1930s,

for the Department store Gamages and maybe for other distributors, with

cosmetic changes to the bed casting but otherwise identical.

Adept Tool Company (Cleveland Ohio) Brochure

Illustration ca. 1930s.

An Australian

version of the Super Adept was sold as the "TNC" after WW2 and

perhaps just before. I have good

reason to believe that this was produced in Australia by Australian lathe

manufacturer Fred Hercus. An Australian

“TNC” brand shaper was also available, and possibly the Adept ordinary lathe

and the rumoured (but never authenticated) Adept horizontal mill. The TNC Super lathe was an exact copy of the

Super Adept except for: (1) a straight (not waisted) carriage leadscrew handle;

(b) “TNC” cast on the base and “British Made” removed; (c) different paint job;

and (d) an improved top slide which greatly simplified taper turning. Fred Portass produced a modified Adept for

the department store Gamages. This was

identical save for cosmetic changes to the bed casting. Other pseudo-Adepts seem to have been

produced.

The design of

Adept lathes changed hardly at all over three decades of production. The pulleys of early specimens have 90°

vee-grooves for the ¼” round leather belting.

This was prone to slippage so later (certainly Post-War) machines had

60° grooves. Most or all of the pre-War

lathes featured an inferior system of securing the slide’s feedscrews. A flat slotted keeper plate, screwed onto

the slide, engaged a groove turned in the knob end of the screw. Eventually the plate wore down and the

groove developed rounded edges. This

caused serious backlash and in bad cases the feedscrew and plate could seize

up. Later lathes had a more expensive

feedscrew, turned from larger diameter stock, with a substantial turned

collar. The plate was no more. Instead, the collar sandwiched the drilled

casting on the inside, with the knob on the outside. Backlash could now be eliminated by altering the knob’s endplay,

then locking with a grubscrew.

Sellers today

often describe Adepts as “watchmaker’s lathes”. Based on this, an unwitting buyer may pay far above what a

well-used specimen of the cheapest lathe ever made is worth. Adepts were far from precision machines, but

some workers especially in the early Austerity years were desperate for any

platform to rebuild, and reconstructed Adepts in impressive machines. The famous model engineering writer and

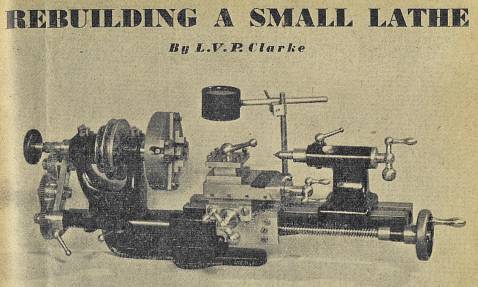

illustrator Terry Aspin wrote of such a conversion. The machine illustrated below was remade by L.V.P. Clarke into a

collet-holding, screwcutting watchmaking lathe of true precision grade. Bear in mind that little remained of the

original but heavily machined and scraped castings. Adepts were certainly made of good quality iron!

Some

speculate that a screwcutting Adept lathe was produced. I agree with Tony Griffiths that many British

workers were able to adapt standard machines to screwcutting. Indeed, the Model Engineer has articles

on how to do this, including making an Adept-based screwcutting watchmaking

lathe! Ah…Those were desperate days in

the Austerity years after WW2. This

accounts for the rare but diverse screwcutting and draw-in spindle Adepts

occasionally seen today.

An ultimate makeover. Model Engineer 17 July

1947.

Manufacturer’s Spares and Accessories

The standard

kit for the Ordinary and the Super models comprised a drive chuck, two male

centres, and in the case of the Ordinary, choice of a bolt-on hand-rest or

slide-rest. Spares were available from

the very beginning. These included

mandrel, top-slide, a pair of male centres, and two-step pulley. In the late 1940s the range of accessories

for the Super (besides countershaft and treadle “foot-motor”) was advertised as

(prices in shillings):

4-jaw independent chuck, 2-1/4” 32/-

3-jaw 'dog chuck' 10/6

Large faceplate, 3-1/4” 6/-

Carrier, 3/8” diameter 2/3

Carrier, 5/8” diameter 2/6

Hand rest 4/-

Prong chuck for wood 4/-

Small angle plate, 2-3/8” x 1-3/8” x 1-1/2” 4/-

Drill pad with vee groove 3/6

Set of three turning tools 3/6

Set of six turning tools 7/-

Round leather belting, per foot 6d

The 1963

Bond's catalogue listed three more accessories which seem to comprise the rest

of the small range: drill chuck, 0-1/4”; three-point steady rest; and pair of

female centres. These were probably old

stock since Adepts were out of production.

The drill chuck and steady were introduced late in the line’s

history. There was never a 3-jaw

universal chuck because the maker could not produce one cheap enough. The foul 3-jaw ‘dog chuck’ was borderline

useless and repeatability was impossible; I have a good specimen so don’t tell

me otherwise.

The light,

four-jaw independent chuck was excellent, but the thinly casehardened jaws wore

down in a few years and users complained in the model engineering press. Usually they take a lot of work to put in

good working order including, sometimes, making new jaws from tool steel with

your Adept hand shaper.

Restoring and Using Adepts

Adepts are

very cute miniature versions of the cast iron engine lathe, minus the

back-gearing of course. My own

enthusiasm for Adepts relates to my interest in retro-modelling the North

Eastern Railway in 7mm scale, using only the limited tools and materials

available to a modeller in the UK during the awful post-War Austerity

decade. This is definitely an exercise

in scratchbuilding and self-discipline.

What better suits this mode than the ultra-basic Adept?

Adepts are

not hard to find, and seldom worth much money, but anyone expecting to use an

Adept must do some elementary toolmaking which usually does not require an

extensive workshop. All Adepts now have

at least six decades of wear so do not expect much. Furthermore, the range of accessories was so limited as to be comical,

since these machines dated from a time when their users were prepared to bodge

up their own accessories and tooling. A

rich literature on upgrades and making accessories and tooling can be found in

pages of the Model Engineer for the

1920s, 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s.

When you buy

an old machine, like an Adept, you roll the dice especially if it cannot be

inspected before purchase. You may not

get far if you lack machinery – or friends with machinery - to recondition

certain components such as chuck jaws (almost always badly worn), taper

sockets, and mandrel (spindle) nose. In

fact you may have to build a new mandrel if only because 3/8” BSF headstock

tooling is rare as hens’ teeth. I am

planning to make a couple with ¾” thread to suit Sherline chucks. Many or all of the tapers that may come with

your machine will likely be scored or otherwise deficient. I recommend making a small 0MT toolroom

reamer and making a full set of taper tooling from scratch. Quarter-inch, unhardened, mild steel rod was

what Fred Portass used for his male and female centres. If like me you really get into restoring

small retro lathes, maybe you can justify to your spouse a Myford to

manufacture spindles, cut ACME screws, and many other high accuracy machining

jobs.

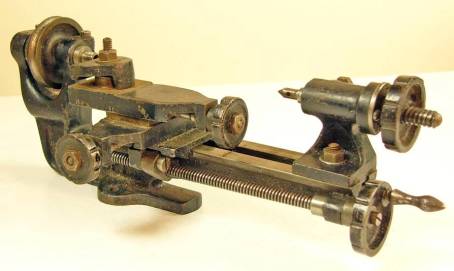

Super Adept as received. Lots of work needed. Collection A. Webster.

Final Thoughts

More

photographs and further descriptions of Adepts can be found at Tony Griffith’s

excellent lathe site http://www.lathes.co.uk/adept/index.html

. The Adept and early Portass pages have

been updated recently to reflect correspondence with Tony. Contact Tony if you have any thing to add on

the early history of the Portass firm – He has a special interest and does a

great service by making lathes information available free on the Internet. He is always interested in interesting

photos, historical information, and literature on old small lathes.

My interests

are more focused. Do contact me if you

are an Adept, Baby Portass, or Pools 3” Special enthusiast and want to share

ideas or knowledge. I endeavour to

share what I learn with other enthusiasts, and I am slowly preparing a book on

restoring and using classic small lathes.

© Andrew

Webster, Ottawa

a.webster@sympatico.ca (Type it in – Not a hyperlink)